Women could potentially one day not play such a vital role in the baby-making process. A fertilisation experiment has shown embryos can be created with skin cells and sperm - the first alternative to a female egg.

This could, in theory, mean that gay men could one day have babies with each other – although they would still need a woman surrogate.

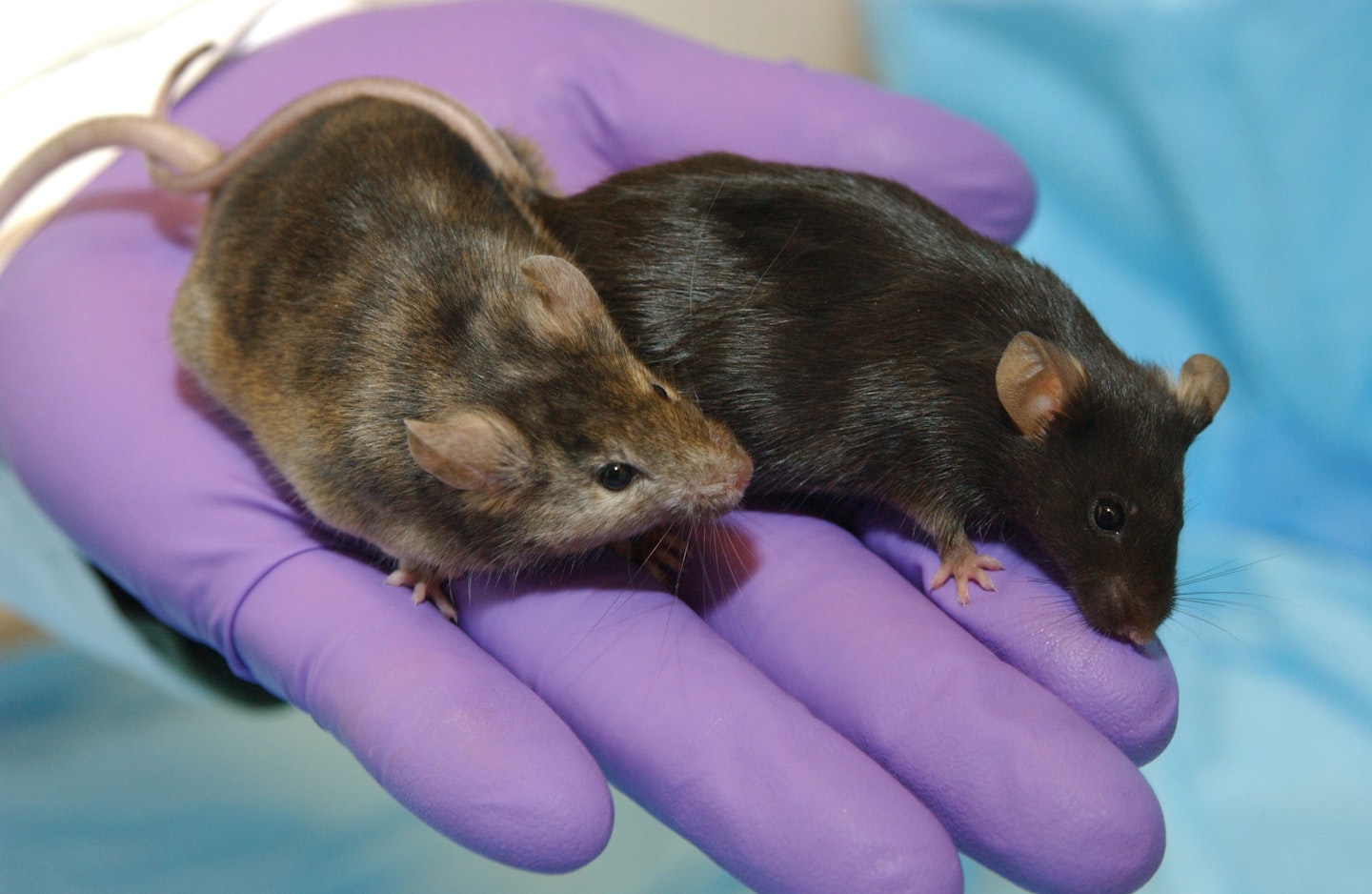

Using mice, scientists have, in a ground-breaking study, appeared to conclude that it would be possible to conceive healthy mice using other kinds of cells and sperm.

The study could also mean that women who cannot conceive due to cancer drugs or other treatment, may still have the chance to have their own children from using cells from elsewhere.

Lead scientist Tony Perry, from the University of Bath, said the experiment on mice only shows the technique would work in principle.

He explained: “Our work challenges the dogma, held since early embryologists first observed mammalian eggs around 1827 and observed fertilisation 50 years later, that only an egg cell fertilised with a sperm cell can result in live mammalian birth.”

The experiment saw “parthenogenetic” mouse embryos created by scientists – which are similar to ordinary cells – injected with sperm and transformed into healthy embryos and offspring.

“The practical applications of this as the technology stands at the moment are not very broad,” Dr Perry said.

“What we’re saying is that these embryos are mitotic cells – mitotic cells are the type of cell that almost every dividing cell in your body is.

“And therefore potentially one day we might be able to extend what we’ve shown in these mitotic cells to other mitotic cells.”

30 pups were born with a 24 per cent success rate, but the molecular embryologist stressed their work was only the beginning: “Will we be able to do that? I don’t know.

"But I think, if it is ever possible, one day in the distant future people will look back and say this is where it started.”

What do you make of the experiment?

Let us know via Facebook and Twitter (@CloserOnline).