Having epilepsy means that you have a tendency to have epileptic seizures.

What is a seizure?

A seizure happens when there is a sudden burst of intense electrical activity in the brain. This is often referred to as epileptic activity. The epileptic activity causes a temporary disruption to the way the brain normally works, so the brain’s messages become mixed up.

What happens to you during a seizure will depend on where in your brain the epileptic activity begins, and how widely and quickly it spreads.

For this reason, there are around 40 different types of seizure, and a person may have more than one type, which means everyone will experience epilepsy in a way that is unique to them.

How seizures affect you depends on the area of your brain affected by the epileptic activity. For example:

Some people lose consciousness during a seizure but other people don’t

Some people have strange sensations, or parts of their body might twitch or jerk

Other people fall to the floor and convulse (this is when they jerk violently as their muscles tighten and relax repeatedly)

Seizures usually last between a few seconds and several minutes. After a seizure, the person’s brain and body will usually return to normal.

Some people only ever have seizures when they are awake. Other people only ever have them when they are asleep. Some people have a mixture of both.

Seizures can start at any age, but are most common in children and older people.

“Triggers”

Some things make seizures more likely for some people with epilepsy. These are often called ‘triggers’.

Triggers can be things like:

-

Stress

-

Not sleeping well

-

Drinking too much alcohol

-

If you miss meals

-

Not taking your epilepsy medicine

-

Lights that flash or flicker

Not everyone has seizures triggers, but for those who do, avoiding triggers lowers the risk of having a seizure.

A person will no longer be considered to have epilepsy if they:

-

Had an epilepsy syndrome that only affects people of a certain age, but are now past that age. An example is benign rolandic epilepsy, or

-

Have not had a seizure for 10 years, and had no epilepsy medicine for five years

Seizure classification

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), a worldwide organisation of epilepsy professionals, has put together a list of the names of different seizure types. This is called the ILAE seizure classification.

Some people use different words to describe seizures. But it is important for doctors to give seizures the right names. This is because specific medicines and treatments can help some seizure types but not others.

Focal seizures

-

In focal seizures, epileptic activity starts in just part of the person’s brain.

-

You might be aware of what is going on around you in a focal seizure, or you might not.

-

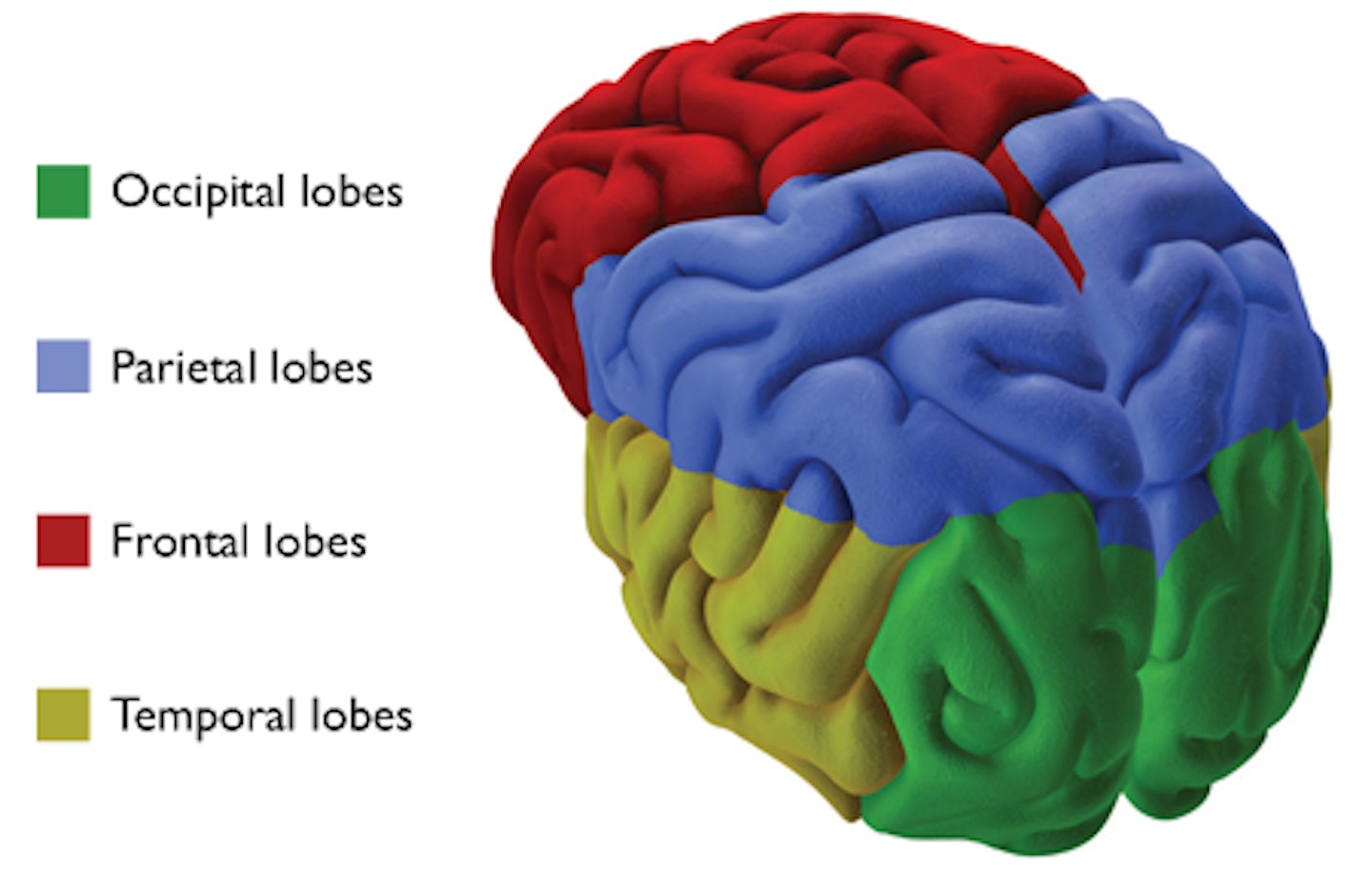

Different areas of the brain (lobes) are responsible for controlling all of our movements, body functions, feelings or reactions.

-

So, focal seizures can cause many different symptoms.

The brain is made up of four types of “lobes”:

Seizures can start in any of these lobes. What happens during a seizure will be different, depending on which lobe, and which part of the lobe, the seizure starts in. Each person will have their own experiences and symptoms during a focal seizure.

For more information on what happens during a seizure depending on these lobes, click here.

Todd’ Paresis (sometimes called Todd’s Paralysis)

-

Todd's paresis is a temporary weakness or paralysis in a hand, arm or leg.

-

It affects some people after they have had a focal or generalised seizure.

-

The weakness can be very mild, or it can completely paralyse that part of the body, or affect vision.

-

Todd’s paresis usually occurs in just one side of the body.

-

It can last from minutes to hours, before going away.

Focal seizures that act as a warning of a generalised seizure

-

The epileptic activity that causes a focal seizure can sometimes spread through the brain and develop into a generalised seizure.

-

If this happens, the focal seizure acts as a warning of a generalised seizure and is sometimes called an aura.

-

The aura is usually brief, lasting a few seconds or so, although in rare cases, auras can last for minutes, hours, or even days.

-

Once the epileptic activity spreads to both halves of your brain, you quickly have a generalised seizure, usually a tonic-clonic, tonic or atonic seizure.

-

Warnings can be very useful. They might give you time to get to safe place or let someone else know that you are going to have a seizure.

-

Sometimes, the epileptic activity spreads to both halves of your brain so quickly that you appear to go straight into a generalised seizure.

Generalised seizures

-

In these seizures, you have epileptic activity in both hemispheres (halves) of your brain. You usually lose consciousness during these types of seizure, but sometimes it can be so brief that no one notices. The muscles in your body may stiffen and/or jerk and you may fall down.

Tonic-clonic seizures

There are two phases in a tonic-clonic seizure: the ‘tonic’ phase, followed by the ‘clonic’ phase:

-

During the tonic phase, you lose consciousness, your body goes stiff, and you fall to the floor. You may cry out.

-

During the clonic phase, your limbs jerk, you may lose control of your bladder or bowels, bite your tongue or the inside of your cheek, and clench your teeth or jaw. You might stop breathing, or have difficulty breathing, and could go blue around your mouth.

Tonic seizures

-

The symptoms of a tonic seizure are like the first part of a tonic-clonic seizure. But, in a tonic seizure, you don’t go on to have the jerking stage (clonic).

Atonic seizures (sometimes called drop attacks)

-

If you have atonic seizures, you will lose all muscle tone and drop heavily to the floor. These seizures are very brief and you will usually be able to get up again straight away.

Myoclonic seizures

-

These are usually isolated or short-lasting jerks that can affect some or all of your body. They are usually too short to affect your consciousness. The jerking can be very mild, like a twitch, or it can be very forceful.

-

Myoclonic seizures often only last for a fraction of a second and you might have a single jerk or clusters of several jerks.

Absence seizures

-

Absence seizures usually develop in children and adolescents. The two most common types of absence seizure are typical and atypical.

Typical absences

-

If you are having a typical absence seizure, you will be unconscious for a few seconds.

-

You will stop doing whatever you were doing before it started, but will not fall.

-

You might appear to be daydreaming or ‘switching off’ or people around you might not notice your absence.

-

You might blink and have slight jerking movements of your body or limbs.

-

In longer absences, you might have some brief, repeated actions.

-

You won’t know what is happening around you, and can’t be brought out of it.

Atypical absences

-

Similar to typical absences, but they last longer.

-

You will have less loss of consciousness, and may have a change in muscle tone.

-

You might be able to move around, but you will be clumsy, and need some guidance and support.

-

You may be able to respond to someone during an atypical absence seizure.

-

People who have atypical absences usually have learning disabilities, other seizure types, or other conditions that affect their brain.

Febrile seizures

Febrile seizures happen to around three out of every hundred children under the age of five. They are usually linked to a childhood illness such as tonsillitis, or teething.

Febrile seizures are not epilepsy. However, children who have had febrile seizures have a slightly higher chance of developing epilepsy later on than children in general.

What to do if someone has a seizure

Watch this video:

For more information on what to do if someone has a seizure, visit Epilepsy Action’s website and YouTube page{

To read more about Epilepsy, try these: